Jho Institute for Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery Department of Neuroendoscopy

Spine Diseases

Brain Diseases

Pituitary Tumor, Pituitary Adenoma: Dr. Jho's Endoscopic Pituitary Tumor Surgery Through a Nostril

Dr. Jho's Minimally Invasive Endoscopic Pituitary Tumor Surgery Through a Nostril for Pituitary Adenomas, Prolactinomas, Acromegaly and Cushing's Disease

Professor & Chair, Department of Neuroendoscopy

Jho Institute for Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery

Mahaley Clinical Research Award in Oct. 2001

Dr. Jho has pioneered to make Transsphenoidal Pituitary Surgery much less invasive by adopting an Endoscope.

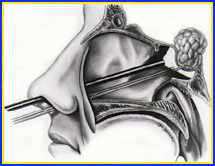

Dr. Jho's endoscopic pituitary surgery is performed through a natural nasal air pathway without any incisions (unlike the conventional microscopic surgery performed with an incision made under the upper lip or inner aspect of a nostril). Endoscopic surgery does not require the use of a metallic transsphenoidal retractor that is used for conventional microscopic surgery. A 4-mm endoscope is placed in front of the tumor in the sphenoidal sinus and the tumor is removed with specially designed surgical tools. Postoperative nasal packing is not necessary and postoperative discomfort is minimal. Most patients are able to go home the following day. The optical advantages of an endoscope (such as a wide-angled panoramic view, an angled view by angled lens endoscopes, and a view in the tumor removal cavity) enhances tumor removal even in complex cases of bulky tumors.

A:  B:

B:

B:

B:

Figure 1. Schematic drawings (A, B) demonstrate techniques of endoscopic pituitary surgery. A transsphenoidal retractor is not used. No skin or mucosal incisions under the lip or nostril are required. No postoperative nasal packing is necessary. Average hospital stay is overnight.

A:  B:

B:

B:

B:

Figure 2. An intraoperative endoscopic picture demonstrates surgical access made between the middle turbinate and nasal septum, paraseptal approach. A surgical instrument indicates the paraseptal route between the middle turbinate and nasal septum (A). The sphenoid ostium is visible in this photo when an endoscope is further navigated through the paraseptal approach (B, arrows).

A:  B:

B:  C:

C:

B:

B:  C:

C:

Figure 3. When an endoscope is placed in the sphenoidal sinus through a small anterior sphenoidotomy via a paraseptal approach, a panoramic endoscopic view (A,B) demonstrates the wide area of the posterior wall of the sphenoidal sinus. This wide-angled panoramic endoscopic view is a quite contrast to the limited narrow visualization of the sella by the conventional operating microscope. Intraoperative endoscopic images present a wide-angled panoramic view of the sella (s), optic nerves (o), cavernous sinuses (cs), clivus (c), and tuberculum sella (ts). After completion of tumor removal, the sella is reconstructed with autogenous bone that was preserved at the time of an anterior sphenoidotomy (C).

A:  B:

B:

B:

B:

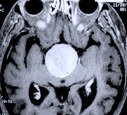

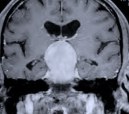

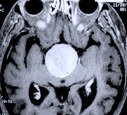

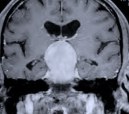

Figure 4. An MR scan, coronal view, shows a large pituitary tumor preoperatively (A). The optic chiasm (arrows) is draped over the tumor. Total tumor removal is demonstrated postoperatively (B). The optic chiasm is now free from compression (arrows).

A:  B:

B:  C:

C:  D:

D:

B:

B:  C:

C:  D:

D:

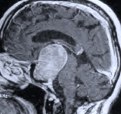

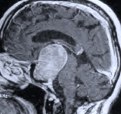

Figure 5. A preoperative axial CT scan shows a large pituitary tumor (A). The patient had previously undergone attempted transphenoidal microscopic removal of the tumor by another surgeon. Only biopsy was possible at that time due to the hard fibrotic consistency of the tumor. The biopsy site is visible at the center of the tumor (arrow). MR scans, axial (B), coronal (C) and sagittal (D) views, show a large pituitary tumor.

A: B:

B: C:

C: D:

D: E:

E:

B:

B: C:

C: D:

D: E:

E:

Figure 6. Although this patient was referred for an invasive craniotomy surgery due to the hard fibrotic nature and large suprasellar protrusion of the tumor, endoscopic transspehnoidal surgery via a nostril was performed instead. Postoperative MR scans, axial (A), coronal (B), and sagittal (C) views, confirm complete tumor removal. The white shadow in the sagittal view (C) is an abdominal fat graft placed at the tumor resection cavity (F). Nasal packing is not necessary and is not used as seen in this patient in the recovery room following endoscopic pituitary tumor surgery (D). The next picture (E) shows the same patient prior to discharge on the day following surgery.

A:  B:

B:

B:

B:

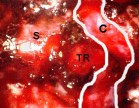

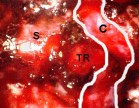

Figure 7. An intraoperative endoscopic image of a patient with acromegaly shows a pituitary adenoma (PA) in the left cavernous sinus (A). This pituitary tumor involving the cavernous sinus was completely removed with an endoscopic endonasal approach ( B, S: sella, TR: tumor resection cavity in the cavernous sinus, C: carotid artery (outlined in white lines). Postoperative cure of the patient's acromegaly was confirmed by endocrinological testing.

A:  B:

B:

B:

B:

Figure 8. An MR scan, coronal view (A), shows a recurrent pituitary tumor involving the left cavernous sinus in another patient. The patient had undergone two previous transsphenoidal surgeries by another surgeon. The patient then underwent an endoscopic endonasal surgery for the recurrent cavernous sinus pituitary tumor. Postoperative MR scan, coronal view (B), shows complete tumor removal from the left cavernous sinus and anatomical preservation of the pituitary stalk and gland.

Anatomy of the pituitary gland

The pituitary gland is a small piece of tissue of dual origin (pharynx for the adenohypophysis and brain for the neurohypophysis) attached to the brain by a stalk. The pituitary gland hangs downward from the brain and dwells in a small cavity known as the sella. The shape of the cavity containing the pituitary gland mimics a Turkish horse saddle (Sella Tursica). The gland is located at the center of the head at the juncture between the cranial cavity and nasal cavity.

Embryonically, it is formed partly from the brain tissue itself (posterior lobe) and partly the throat tissue (anterior lobe). Once they are joined together during the developmental stage in a fetus, it forms the pituitary gland as a whole. The cherry-shaped pituitary gland is attached by a stalk (pituitary stalk) to the base of the brain, the hypothalamus. The posterior lobe, also known as the neurohypophysis, is directly connected to the hypothalamus by the pituitary stalk.

Just above the pituitary gland lie the continuous visual nerve cables such as the right and left optic nerves, the optic chiasm which are the conjoined crossing cables, and the optic tracts which are the visual nerve cables conducting visual impulses to the brain. Just above the visual system is the hypothalamus, which is the vital brain tissue controlling homeostasis (maintenance of equilibrium-like conditions such as temperature and other parts of the autonomic nervous system, appetite, etc.) and instincts of the human body.

Details of pituitary gland function

The hypothalamus produces hormones such as vasopressin (ADH) and oxytocin. Vasopressin or antidiuretic hormone (ADH) generally controls water balance, depending on the degree of blood concentration (osmolality), by acting primarily on the kidneys. Oxytocin functions by stimulating womb muscle contraction during the delivery of a baby and in releasing milk from the breasts of a nursing mother. These hormones are transported from the hypothalamus of the brain to the posterior lobe (neurohypophysis) of the pituitary gland via the pituitary stalk.

The anterior lobe (adenohypophysis) produces many different hormones under the influence of numerous other stimulating hormones that are transported via the arterial blood stream. The releasing hormones produced by the hypothalamus travel via an arterial blood stream to the anterior lobe. These releasing hormones stimulate the production and release of hormones in the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. Hormones produced in other parts of the body can also influence the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland via the blood stream.

The pituitary gland is the center of hormonal control of the entire body. The adenohypophysis produces many hormones such as adenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), growth hormone (GH), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and prolactin (PRL).

Production of ACTH is controlled directly by hypothalamic production of corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH). ACTH stimulates the adrenal gland (which is located just above the kidney) to produce corticosteroid hormones, which are vital hormones for maintaining physical integrity and coping with physical stress. ACTH is counterbalanced by the production of corticosteroid hormones (negative feedback). Complete stoppage of ACTH production is fatal causing so called "Addisonian crisis" if medical treatments with replacement steroids are not instituted immediately. Addisonian crisis is a condition of shock related to the lack of corticosteroids in the body.

TSH is produced by the stimulation of a hypothalamic hormone named thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH). TSH stimulates the thyroid gland in the neck to produce thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormones generally have a role in maintaining metabolic homeostasis and have a counterbalance effect to the production of TSH in the pituitary gland (negative feedback).

LH and FSH controls production of female sex hormones such as estrogen and progesterone as well as the production of testosterone. These sex hormones generally function to produce sexual characteristics and the reproductive cycle, and also have counterbalance effects to the pituitary gland (negative feedback).

Prolactin is a hormone acting in milk production. Prolactin secretion is high in a woman during lactation for a newborn baby. Overproduction of prolactin can result in aberrant milk production (even in males) and significantly decreased libido. Dopamine produced in the brain is the natural negative regulator of prolactin production, and therefore dopaminergic agonists (such as bromocriptine) are used as medical treatments for overproduction of prolactin.

Although other hormones are produced in the pituitary gland, the aforementioned pituitary hormones are the important ones for the maintenance of body integrity.

Pituitary tumors

Many types of tumors can occur in the pituitary gland. The most common tumors in the pituitary gland are pituitary adenomas (which are benign). However, metastatic cancer can dwell in the pituitary gland when the cancer cells metastasize to the pituitary gland.

Benign pituitary adenomas can be divided into nonfunctioning tumors and functioning tumors depending on the capability of tumor cells to produce hormones. Nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas do not produce active hormones by themselves. Nonfunctioning tumors mechanically compress surrounding structures such as normal pituitary gland and optic system. Functioning pituitary adenomas produce a hormone(s) in excess. Excess amount of hormone produced by tumor cells cause symptoms dependent on the type of hormone. Functioning pituitary adenomas include prolactinomas (PRL overproduction), adenomas that cause Cushing's disease (ACTH overproduction), adenomas that cause gigantism or acromegaly (GH overproduction), and TSH-producing tumors.

Prolactinomas are the most common functioning pituitary adenomas and produce excess amount of prolactin that results in amenorrhea (irregular menstrual periods), breast discharge (galactorrhea), infertility, and sexual dysfunction.

Pituitary adenomas that produce ACTH cause Cushing's disease. Symptoms of Cushing's disease include ruddy moon face, truncal obesity, buffalo hump, hypertension, abdominal striae, easy bruisability, depression, psychosis, irregular menses, impotence, osteoporosis, muscle weakness, etc. Cushing's disease is a serious condition requiring prompt treatments.

Pituitary adenomas that produce growth hormone cause gigantism in children (due to still active growth plates) or acromegaly in adults. In acromegaly the jaw, cheeks, fingers, and toes are thickened along with the enlargement of soft tissues such as the tongue, nose, and lips. Affected adult patients might find that their shoes or hats do not fit properly any longer.

TSH-producing adenomas, which are relatively rare, cause goiters (enlarged thyroid gland) and thyroid hyper-function disorders.

Symptoms of pituitary tumors

Symptoms of pituitary tumors are: 1) Hormonal disorders from excessive production of hormones from the tumors, 2) Pituitary hormonal dysfunction from compression of the normal pituitary tissue, 3) Visual disorders from tumor compression of the optic system, 4) Other symptoms related to the compression of the surrounding brain such as the hypothalamus.

When functioning pituitary adenomas produce hormones, the excess amount of hormone will cause particular hormonal disorder symptoms depending on the type of hormone as described earlier. When pituitary adenomas become large, they compress and make the normal pituitary gland tissue hypo- or non-functional (hypopituitarism) resulting in pituitary hormonal dysfunction. Most often, nonfunctioning adenomas grow to large sizes undetected and result in hypopituitarism. However, functioning adenomas can also cause general hypopituitarism even while producing an excess amount of a particular hormone.

When pituitary tumors compress the optic system (which is located just above the pituitary gland), visual disorders may develop. The most common visual disorder is a visual field defect at the outside view of each eye known as bitemporal hemianopsia.

Other symptoms such as memory disorder, hydrocephalus, and other brain dysfunction can develop if the tumor is large enough to compress the hypothalamus. Pituitary adenomas are known to bleed spontaneously (pituitary apoplexy). When spontaneous bleeding occurs inside a pituitary adenoma, symptoms of severe headaches, visual disorders, eye movement disorder, and altered consciousness can develop. Immediate medical treatment is necessary and surgical treatment is often required.

Treatments of pituitary tumors

Medical, surgical, and/or radiation treatments are available for pituitary tumors. Prolactinomas can be treated with medications (bromocriptine is most commonly used). Surgical treatment is indicated when medication side effects or intolerance develops. Acromegaly can be treated with octreotide medication but does not respond as well as prolactinomas do with bromocriptine. Often, acromegaly requires surgical removal of the tumor. If surgery is not successful, octreotide medication or radiation treatment (gamma-knife surgery) can be considered. Cushing's disease requires surgical removal of the tumor as the first line of treatment. If surgical treatments fails to relieve symptoms, radiosurgery or medical treatments can be instituted. TSH-secreting adenomas require surgical treatment. When nonfunctioning tumors cause symptoms, surgical treatment is the first choice among the treatments. If surgical treatments are not successful, radiation treatment (conventional radiation or radiosurgery) has to be considered.

Conventional transsphenoidal surgery has historically been performed under the operating microscope via an incision underneath the upper lip (sublabial incision) or intranasal incision (transfixional incision). It requires two to three days of nasal packing and three to five days of hospital stay. Dr. Jho has developed a new surgical technique that utilizes an endoscope instead of the traditional operating microscope. Endoscopic pituitary tumor surgery is performed through a nostril without conventional incisions. After surgery, nasal packing is not required. Postoperative discomfort is minimal. Often, hospital stay is overnight.

Facts About This Surgery

Discussion

Endoscopic pituitary surgery can be performed for various types of pituitary tumors such as prolactinomas, Cushing's disease, gigantism or acromegaly, non-secreting adenomas, and for pituitary adenomas invading the cavernous sinus or extending into the suprasellar region. The conventional surgical methods for removal of pituitary adenomas involve incisions under the upper lip or in the nostril. This requires the use of postoperative nasal packing.

Adapting the use of a small fiberoptic-like catheter shaped tool called an endoscope, a surgical procedure has been developed that not only eliminates the need for nasal packing but heightens the surgeon's visualization of pituitary tumors. Replacing the bulky operating microscope, the endoscope provides the surgeon with a panoramic view of the pituitary gland and surrounding structures. It can also provide a very close view of the pituitary gland and tumor interface. The patient undergoes general anesthesia, the endoscope and surgical instruments are placed in the patient's nostril, and the tumor is removed. No lip or nasal incisions are made, no packing is placed, and patients are generally sent home the day after surgery. Patients can usually return to work or school in four to six weeks time.

Definitions

adenoma - a benign slow growing tumor of the pituitary gland.

References

Practice Manager: Robin A. Coret

Tel : (412) 359-6110

Fax : (412) 359-8339

Address : JHO Institute for Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery

Department of Neuroendoscopy

Sixth Floor, South Tower

Allegheny General Hospital

320 East North Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15212-4772

Copyright 2002-2032